- Luxor Attractions

- Shoroq Samir

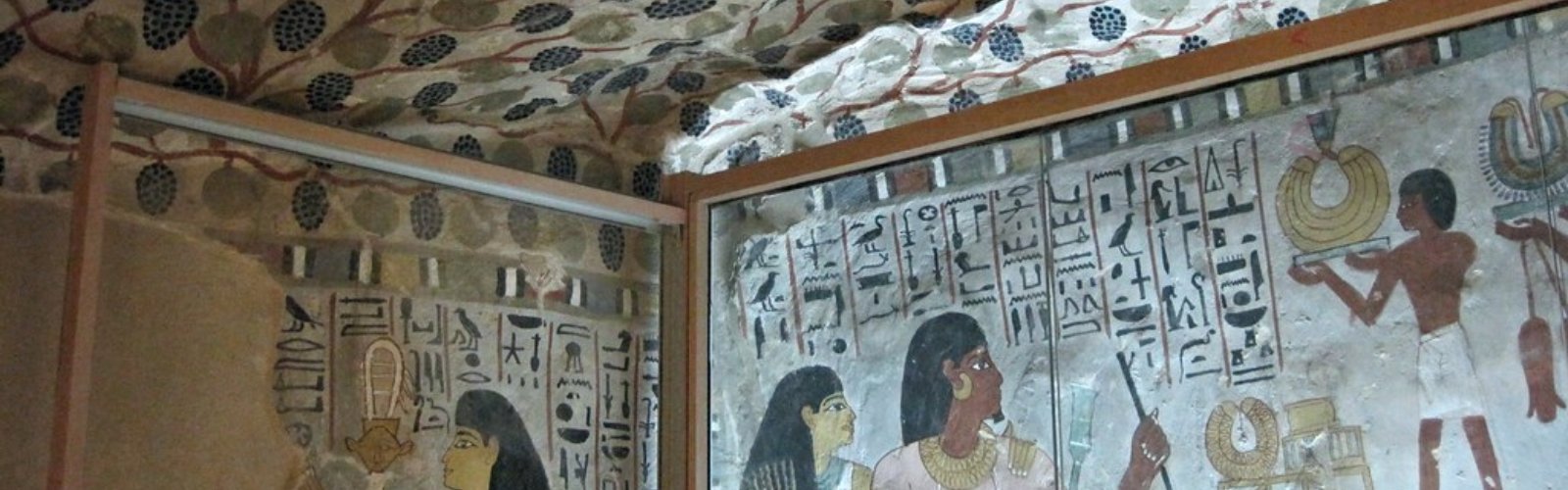

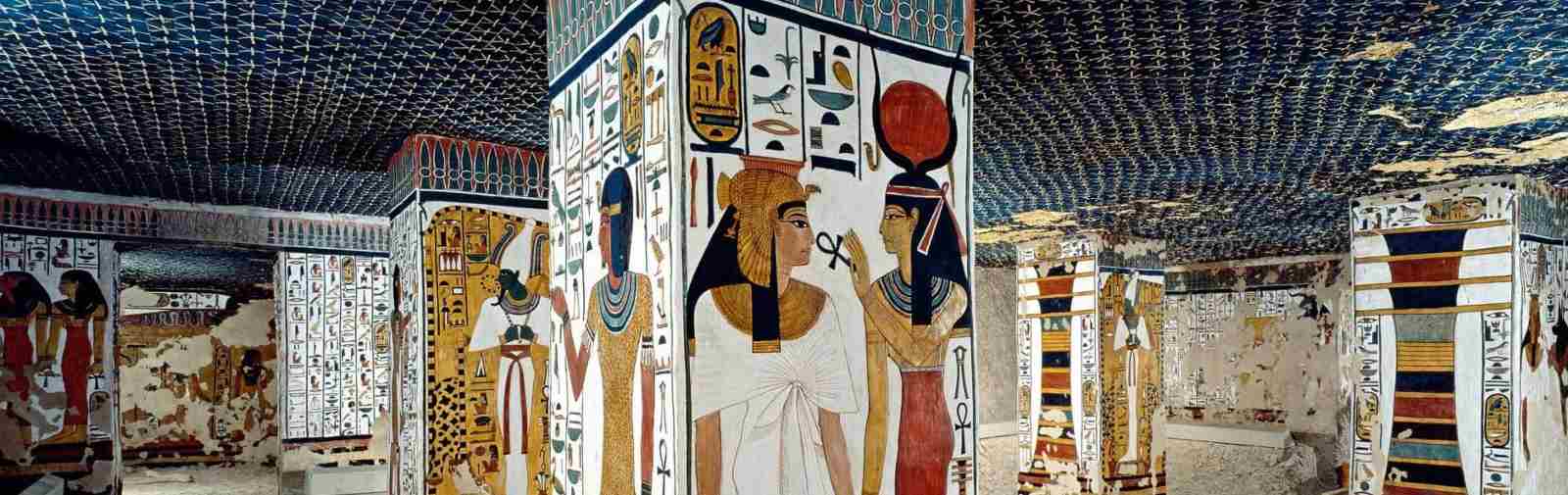

Karnak Temple in Luxor Egypt

Karnak is the biggest temple complex in the world, covering an area of 100 hectares and there is nowhere more impressive to the first-time visitor. Much of it has been restored during the last century and our knowledge of the buildings here in different periods of Egyptian history is still increasing each year. In ancient times, Karnak was known as Ipet-isut, ‘The most select of places’.

Karnak Temple interior design

The temples are built along two axes (east-west and north-south) with the original Middle Kingdom shrines built on a mound in the center of what is now called the Temple of Amun.

On The West Side

the entrance to the temple used by visitors which was once a quay built by Rameses II to give access via a canal to the river Nile. This is where boats carrying statues of the gods would have arrived and departed from the temple during festivals, such as Opet, and from where the cult statue of Amun would leave on its weekly tour of the west bank temples such as Deir el-Bahri and Medinet Habu. There are many names of kings on the quay each recording the levels of inundations during their reigns.

On the right

in front of the first pylon is a small barque shrine built by Hakor in Dynasty XXIX, which was used as a resting place during the gods’ processional journey to and from the river.

An avenue of ram-headed sphinxes lead the visitor towards the massive front of the first pylon, each one holding a statue of the king, Rameses II, in its paws (later usurped by Pinudjem of Dynasty XXI ). The sphinxes were fantastic beasts with the body of a lion and the head of a ram, a symbol of the god Amun.

The First Pylon

It is unfinished and its height, originally of 43m is still pretty impressive. There is no certainty as to who built it, but it’s thought that it may have been the Dynasty XXV king Taharqo whose buildings are in the forecourt. Alternatively, it may have been constructed by Nectanebo I of Dynasty XXX who built the temenos walls which link to the pylon and surround the temple complex. The remains of a mudbrick ramp can still be seen on the inner side of the pylon, the only example we have, and which shows how the pylon was constructed.

The Forecourt

is now inside the entrance pylon but would have originally been outside the main temple. In the centre are the remains of the giant Kiosk of the Nubian pharaoh, Taharqo, with its one complete papyrus column still standing. It is worth remembering that Karnak Temple was built to expand outwards from a central core, the oldest part being in the middle of the main axis, behind the sanctuary of Amun.

To the north of the forecourt and adjoining, the first pylon is the triple barque shrine of Seti II, with three rooms built to contain the barques of Mut, Amun and Khonsu, the gods of the Theban triad.

On the south side of the forecourt is the entrance to a temple of Rameses III, who was not satisfied with the simple way-stations of his ancestors and built an elaborate barque shrine designed as a mini-version of his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu on the west bank. Its first court is lined with Osiris statues of Rameses and its walls show festival scenes and texts. Next to this is the ‘Bubastite gate’, built by Sheshonq of Dynasty XXII, the biblical king ‘Shishak’.

The Second Pylon

was built by Horemheb but not completed until the reign of Seti I. Seti’s son Rameses II built two colossal statues of himself which stood in front of the pylon gate. A third statue of Rameses II still stands in situ and has a tiny statue of his daughter Bent’ anta between its feet. This statue was later usurped by Rameses VI then the High Priest Pinudjem I. Inside the walls of this pylon many of the sandstone talatat blocks from the Akhenaten, the temple was found which had been reused as infill in the construction of the walls.

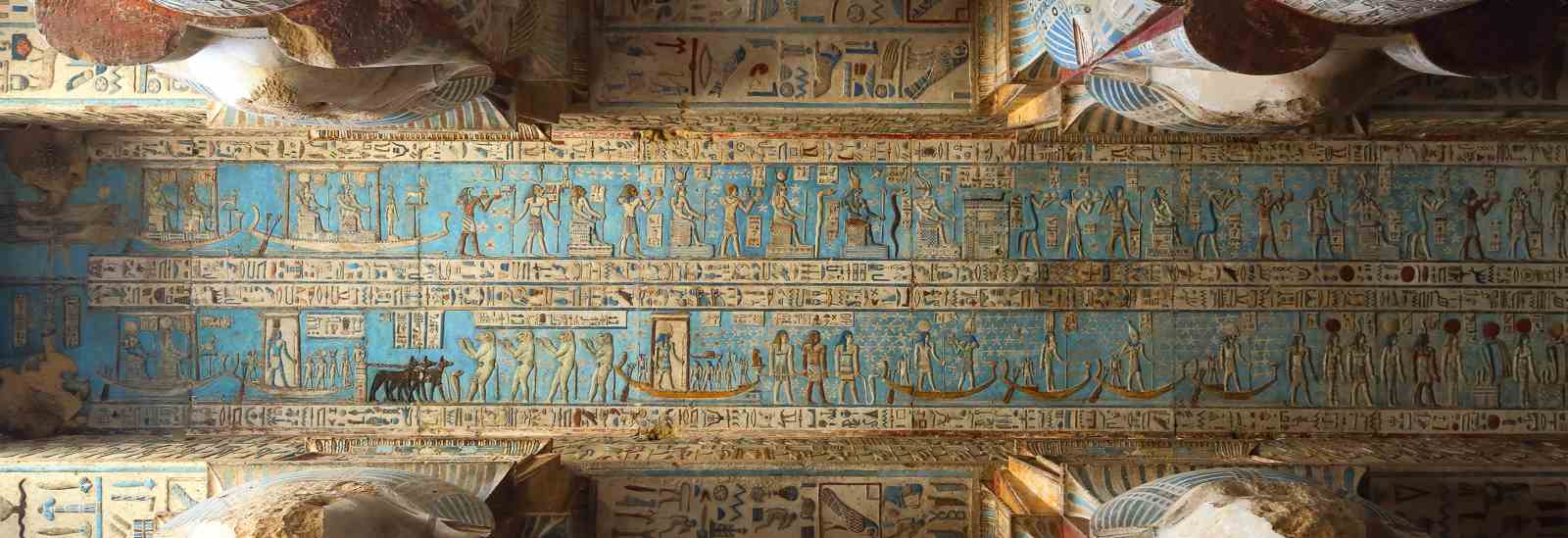

Through the entrance of the second pylon is the famous hypostyle hall. Standing amongst its 134 gigantic columns the visitor can’t help but be awe-inspired by the grandeur of the place. The center 12 columns are larger (21m tall) and have open papyrus capitals, which may have been intended to symbolize the original ‘mound of creation’. The other 122 columns are smaller (15m) and have closed capitals, perhaps representing the swamp which surrounded the mound.

The hypostyle hall

was begun by Amenhotep III who built the side walls which close off the space between the second and third pylons. It was not completed until the reign of Seti I who carved his beautiful raised reliefs around the walls of the northern half. His son Rameses II completed the decoration of the southern half of the walls and pillars, often overcarving his father’s reliefs with his own crude sunk relief carvings including temple foundation rituals. ‘Rameses the Great’ was not going to be forgotten.

Both Seti and Rameses have left us fine examples of temple rituals and the relationship of the pharaohs with their gods. Accounts of their battle exploits are carved around the outer walls. It was Rameses who added a roof of stone slabs to the hall and we can imagine the dim, mysterious atmosphere it would have had, lit only by the high clerestory windows. The pillars are very close together and it’s difficult to get an overview of the hypostyle hall. When it was in use the spaces between the columns would have been filled with statues of gods and kings. Looking back at the hypostyle hall from beyond the third pylon we can see just how high it must once have been.

The third pylon

was built by Amenhotep III and beyond this to the east, we move towards the older part of the temple, built in early Dynasty XVIII. Many reused blocks have also been found inside the third pylon from buildings which are now being reconstructed in the open-air museum. One of a pair of obelisks of Tuthmose I is still standing in the area between the third and fourth pylon and the bases of a pair belonging to Tuthmose III can also be seen. The north-south axis of the temple branches off from this court.

Fourth, Fifth And Sixth Pylon

It seems that each successive pharaoh was compelled to build bigger and better than his forebears. As we get closer to the sanctuary area, the original Temple of Amun, the pylons get smaller and closer together. The fourth and fifth pylons, built by Tuthmose I are much smaller than the third and the area between them is the oldest extant part of the temple. This area was once a pillared hall containing wide papyrus columns – perhaps the prototype of the hypostyle hall and had huge Osiris statues of Tuthmose I lining its walls. It was later restored and added to by various pharaohs, including his daughter Hatshepsut who built two red granite obelisks here, one of which still remains, and the pyramidion of the other lies on its side near the sacred lake. The texts on Hatshepsut’s obelisk give important details of the building of the monument from a single piece of granite and gilded with the finest gold. It is dedicated to her father Amun and it attempts to legitimize her claim to the throne.

Not much remains of the sixth pylon which was built by Hatshepsut’s successor, Tuthmose III, apart from texts giving details of captured prisoners on its lower walls. The area before the sanctuary contains two beautiful pillars, sometimes called the pillars of the north and south, erected by Tuthmose III. The northern pillar shows the emblem of Lower Egypt, the papyrus, and the southern one is the lily (or Lotus) of Upper Egypt.

The sanctuary

It now standing is a granite barque shrine which was built by the Greek Philip Arrhidaeus and replaces an earlier shrine of Tuthmose III. The rooms surrounding the shrine were built by Hatshepsut, who had constructed an even earlier shrine here. If we walk around the passage we can see a statue pair representing Amun and Amunet, dedicated by Tutankhamun and thought to show the face of the boy-king.

The Open Area (journey inside the temple)

It behind the granite sanctuary is the oldest part of Karnak Temple were the earliest sanctuary once stood, right at the heart of the Temple. In the Middle Kingdom a shrine of Senwosret I stood here but the area was robbed for its stone and all that remains is a large alabaster slab which would have had a shrine built on it. The central court is surrounded by various semi-ruined chambers which contain a wealth of fragmentary but interesting reliefs if you have time to explore them.

Following a paved path along the south side of the central court, the visitor will come to a building known as the Festival Temple of Tuthmose III anciently called ‘Most splendid of Monuments’ and built as a memorial temple to Tuthmose and his ancestral cult. The pillars inside the hall are said to imitate the ancient tent poles of a pavilion, unique in Egyptian architecture, and still show good remains of the coloured decoration. One of the rooms to the southwest of the pillared hall once contained a table of kings which listed the names of 62 kings and is now in the Louvre in Paris. There are several ruined statues to the north of the hall, in an area which was used as a church in the Coptic era. Behind the columned hall is a suite of rooms dedicated to Amun. A larger room to the north is sometimes known as the Zoological Garden, or Botanical Garden, because it contains superb delicate carvings representing plants and animals which Tuthmose encountered on his Syrian campaigns.

A flight of wooden stairs lead over the wall behind the festival temple. In the area leading towards Karnak’s east gate is a small ‘Temple of the Hearing Ear’, built by Rameses II. Here local inhabitants of Thebes would bring their petitions to the gods of Karnak, or rather to the priests who would intercede. This was a tradition suggested by earlier niche shrines built against the back of the Tuthmose complex.

Also just inside the crumbling eastern walls are various remains of later temple structures such as a Colonnade built by Taharqo. The Eastern gate must have been once imposing but is now in quite a ruinous state. Beyond this gate and outside the main temple walls, the scant remains of Amenhotep IV’s (Akhenaten) Karnak temple buildings were discovered. These were excavated in the 1970s and many of the colossal statues of Akhenaten now in the Luxor and Cairo museums came from here.

Following the walls round to the north, we come to the Temple of Ptah. The original three sanctuaries were constructed by Tuthmose III and dedicated to the Memphite god, Ptah. It was restored by the Nubian king Shabaqo and later much added to by the Ptolemies and Romans. There are Ptolemaic screen walls and flowered columns in front of the original sanctuary area. The north and center sanctuaries were dedicated to Ptah and the southern one to Hathor. Today, in the southern shrine which is usually now kept locked, is a beautifully restored statue of the lioness goddess Sekhmet.

Beyond the temenos wall to the north is the derelict Precinct of Montu, who was the earlier falcon-headed god of the Theban area before Amun gained prominence. The temple was originally built by Amenhotep III and his cartouches can still be seen on some of the blocks in the compound. Several later kings added to the temple and a large propylon gate was built by Ptolemy III in the quay area to the north. There were many smaller adjoining chapels and shrines dedicated to various deities, as well as an avenue of human-headed sphinxes to the north.

Moving west, past the shrines of the ‘God’s Wives of Amun’, we come to the Open Air Museum which houses various blocks and reconstructed shrines found in other parts of Karnak. Most of the fragments here were found inside the second and third pylons or on the floor of the court of the seventh pylon.

The limestone barque shrine of Senwosret is an airy structure, built as a ‘way-station’ for the king’s jubilee. On its beautifully carved square pillars, we see the king offering to Amun in his ithyphallic form. Next to this is a shining white alabaster shrine built by Amenhotep II, a much simpler construction, and also a similar shrine built by Tuthmose IV. Also here, archaeologists are reconstructing parts of a Temple of Tuthmose IV towards the back of the museum, which are showing some very fine reliefs. One of the most recent reconstructions in the open-air museum is the ‘Red Chapel’ of Hatshepsut which was the original Sanctuary of Amun at the heart of Karnak. It was dismantled by Tuthmose III who rebuilt his own sanctuary, reusing Hatshepsut’s door jambs. Later Amenhotep III made use of the red chapel’s blocks as part of the filling of his third pylon, which is why they have survived in such good condition. French archaeologists have spent the past few years rebuilding the chapel from the available blocks – a very difficult task due to the original construction techniques.

On the other side of the Temple of Amun, to the south, the visitor comes to the Sacred Lake. The area in the foreground was originally a fowl yard and the domesticated birds belonging to Amun were driven from here through a stone tunnel into the lake each day. The lake is overlooked by seating for the Sound and Light show today, but underneath here the remains of priests’ houses were found.

Seventh, eighth and ninth Pylons

Pylons seven, eight, nine and ten runs on a north-south axis to the main temple, called the transverse axis. When the court before the seventh pylon was excavated, a treasure store of 751 stone statues and stelae were found, along with over 17,000 bronzes which now form a large portion of the Cairo Museum collections. Some of the statues can now be seen in the Luxor Museum. They were probably buried in the Ptolemaic Period, but no-one knows exactly why.

The way through the eighth to tenth pylons is blocked due to work in progress. The ninth pylon at present is being painstakingly taken down and reconstructed. Blocks from local Aten temples were used as infill here and we can see some of these talatat blocks of Akhenaten now in the Luxor Museum. To the east of the ninth pylon is a chapel commemorating Amenhotep II’s jubilee, restored after the Amarna Period by Seti I.

In the south west corner of the Amun precinct we come to the Temple of Khonsu – ‘son’ of Amun and Mut, a well preserved small temple from the late New Kingdom, built towards the end of the Ramesside Period. The temple has the feeling that it is a built-in miniature, with squat pillars and low ceilings, which seems appropriate for Khonsu, the child. Reliefs in the rooms to the back of the temple still have some good colours, including this unusual depiction of a lion-headed ithyphallic god.

A doorway from the Khonsu Temple leads through to a later structure adjacent to it. This is a temple dedicated to the hippopotamus goddess Apet, or Opet (not to be confused with the festival of Opet). She is said to have helped women in childbirth, possibly a later aspect of the goddess Tauret. Reliefs inside the temple, however, depict the funeral rites of Osiris, in the Graeco-Roman tradition.

Karnak can be a confusing place, its buildings spanning a long period in Egyptian history. Most visitors on guided tours with travel to Egypt have very little time to see much of the temple, and many visits are needed to get even a brief idea of the temple as a whole.